British Columbia issues combined ID for driver license, health, online use

Contactless EMV to enable non-payment functions

05 June, 2014

category: Contactless, Government, Library, Smart Cards

The Province of British Columbia was in a bind. It had a health ID card that was more than 20-years-old with practically no security features and little identity vetting on the backend.

The province is home to 4.5 million residents, yet had issued 9.2 million BC Care Cards. While some were justifiable duplicates, there were still too many cards floating around in the system. “Basically there were a lot of cards and suspected misuse of the health card,” says Kevena Bamford, executive director for the Provincial Identity Information Management Program in British Columbia. “The Ministry of Health was challenged to replace the Care Cards, strengthen the process of getting the card and incorporate more security features.”

While this was happening, the Ministry of Technology, Innovation and Citizens’ Services was looking to expand the functionality of their BCeID service, Bamford says. The BCeID is an online credential that citizens can use to access government services. Typically it was a low-level, self-asserted credential that takes the form of a username and password combination that was federated for use across provincial online services. The citizen could conduct in-person vetting to raise the level of assurance underlying the username and password login. Unfortunately, few citizens opted for this in-person vetting.

Like the BCeID, the Care Card was typically a low security, level one credential. So the Ministry of Technology, whose primary function is supporting other agencies with the delivery of their technology solutions, started to work with Ministry of Health. The goal was to improve the security of the BC Care Card while also increasing the usability and identity assurance behind their eID service.

Enter the ICBC Driver Licensing Services. Every half-decade a license expires and the citizen must show up to renew the credential and provide foundational documentation. Thus, this is the one government agency that has both in-person contact with citizens and has access to the documents that prove citizen identity.

The ministry saw a chance to kill three birds with one stone. When citizens came to renew their driver license, the same foundational documents could be used to receive a health ID card and increase the assurance level of the eID, Bamford says.

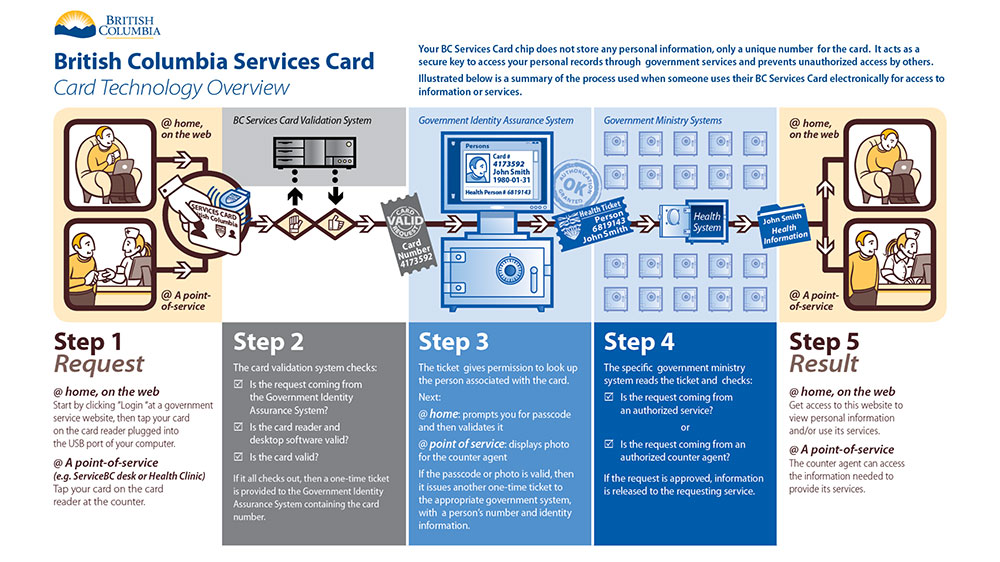

Then came another idea. What if one card was used for all three functions? Thus was born the BC Services Card: driver license, health ID and electronic ID all rolled into one contactless smart card that serves as an extremely strong, level three credential.

By the close of 2013, the province had issued 800,000 BC Services Cards, Bamford says. Residents can choose to combine their driver license and Services Card, or have a standalone Services Card. All Services Cards replace the prior Care Card with improved identity proofing and security features and also enroll citizens in the digital identity program. The contactless smart card has an EMV application stored on it that will eventually be used to authenticate an identity.

Uptake on combination cards has been a little slower than expected, Bamford says. There are businesses around British Columbia that require two forms of identification and two of the most common pieces are the driver license and health ID card. Spreading the word to businesses regarding acceptance of the new combination card has been slow.

British Columbia is working with SecureKey to enable the BC Services Card to be used for access to online provincial services. SecureKey also has a contract with the Canadian federal government to enable contactless bank EMV cards to be used for access to federal services, and there is potential to enable the BC Services Card for access to federal resources as well, Bamford says.

The province is working to build authentication service functionality and business cases so the card can be used to digitally access online services, she explains. At the moment, however, the chip is yet to be used. Still, significant value has been gained based on the fact that all 800,000 eID holders have undergone the stronger in-person identity vetting.

The goal is for citizens to have NFC readers attached to their computers where they could tap the card, enter a passcode and then gain access to online government services. One day, citizens might do the same thing at a doctor’s office to authenticate their identity in order to receive health services.

Government officials are working on the authentication services and business requirements that will enable the smart card’s use, Bamford says. Citizens are being asked how they expect the services to work and what services they would like to see offered.

The results are mixed, particularly around the area of usage history, Bamford says. “Many people in the early focus groups said they would expect to access usage history, similar to a bank account’s transaction history,” she explains. “Others refuse this concept outright, claiming it’s a compromise of privacy and personal security.”

Over the course of 2014, the province plans to work with programs and begin to roll out some digital services that can leverage the authentication service, Bamford says. “Citizens of British Columbia are very interested in using the card,” she adds. “There are many years ahead of us in building the system as well as dialogue around using the credential.”

Related: BC’s Citizen engagement: A model for future programs

Using the BC Services Card to access online services